*

Gentrification is a hot topic these days. Every time a new business opens, the conversation starts anew. Since 2017 began, Ypsi Facebook has blown up with massive threads sounding the alarm about “gentrifried chicken” (as was the case when Ma Lou’s Chicken was set to open) and fears of a “dystopic Ann Arbor future” of hot yoga and hundred-dollar juice cleanses (Tiny Buddha and babo).

Social media agitation gets the goods, if by “goods” we mean increased conversation and media attention to the ever-pressing matter of gentrification. It only took a handful of high-traffic posts on Facebook and Instagram to get the attention of prominent area newsmedia. Early in May, the Detroit News ran an article with a sub-headline that read “Ann Arbor spillover stirs fears of gentrification.” Before that, the Detroit Metro Times, MLive.com, and MarkMaynard.com ran stories. A reporter for Concentrate posted in the Ypsilanti Area Discussion Facebook group just recently that he was “working on a story about the changing commercial and residential markets in Ypsilanti” and was “looking for people or businesses who have been priced out of the City of Ypsilanti, or who are feeling the pinch of increased rents.” Hot chicken, hot yoga, and hot-button socio-political themes.

The most heated conversations tend to happen when an Ann Arbor-based entrepreneur opens up a new business. The patterns of gentrification are well known and we can see them in play when grad students and entrepreneurs move from Ann Arbor to Ypsi for cheaper rent, all the while pricing out folks who’ve already been here. Yet while fears of Ann Arbor spillover are key to understanding these discussions, it is fully possible for an Ypsi resident or native to be complicit in gentrification. Because gentrification is a matter of wealth and whiteness, an entrepreneur living in Normal Park or Depot Town is just as complicit as a business owner who is branching off from Ann Arbor to Depot Town. If you have capital and establish a business that draws in white, class-privileged people, you are complicit.

Yet to be complicit doesn’t mean that one is a bad person or of ill intention. Being complicit means that one is swept up in a larger system that is fundamentally inequitable. Being complicit means that one is acting in accordance with the desires, prerogatives, and consumption habits of those who stand the most to benefit from increased development and rising property values.

For example, Cultivate Coffee & Tap House has a charitable mission, but with fancy toast, craft beer, and $6 pourovers, the combination of high price point, artisanal focus, and cultural programming is going to draw a certain (largely white, gentrifying) clientele of creatives, professionals, and suburbanites. No amount of charitable giving can erase the cost of making Ypsi attractive to people who are able to pay rents that are no longer affordable to the very people whom charitable organizations purport to benefit. Yes, it’s good to talk about concerns of Ann Arbor spillover. But even in the case of local businesses (those businesses whose proprietors are Ypsi residents in good standing with the community), you can sure bet there’s been talk (even if only in whispers) about these businesses being gentrifying. This is not to say that Cultivate doesn’t offer programs of social benefit or give money to organizations doing good work. It does these things while being swept up in larger processes of gentrification. The moral complexity of questions of complicity in gentrification means that even good and well-intentioned people act within and according to the logic of stratifying social systems.

Concerns about gentrification aren’t new. Before the winter and spring of this year, there was the summer and fall of 2015. It was then that the Convention and Visitors Bureau unveiled its #YpsiReal campaign and threw up banners around town and released a promotional video that many regarded as a “commercial for gentrification” (to quote one Facebook commenter). While many at the time were angered about the county merging CVBs, there was little talk at the time of how the CVB as an institution is implicated in the very municipal growth machine that drives gentrification and displacement.

In addition to the CVB merger and the #YpsiReal campaign, summer/fall 2015 was when a globe-trotting entrepreneur with a big imagination opened Lampshade Coffee and a group of professionals with a soft spot for nonprofits opened Cultivate (which itself grew out of a church ministry). While Lampshade no longer exists, Cultivate/#YpsiReal/Lampshade collectively felt like a flashpoint in the ongoing saga of gentrification in Ypsi, much in the same way the trifecta of Cross Street Coffee, Ma Lou’s Fried Chicken, and babo/Tiny Buddha has been this year. A handful of people sounded the alarm back in 2015, though cries of gentrification have since grown louder and in number. This is why the question, “why all the cries about gentrification now and not before?” is silly: people have been sounding the alarm for a while and if one is just hearing this stuff now, it’s because the situation is intensifying, not because people have been silent.

When these conversations pop up, many question whether the targeting of small businesses like babo or Ma Lou’s is the most “productive” route in combatting the inequities produced by gentrification. Critics of gentrification get accused of vilifying business owners and being unwelcoming of outsiders, of being resistant to “change,” or of practicing selective outrage. Many argue that it’s misguided to focus on small businesses as the central agents of gentrification when really it’s a deeper question of public policy, development, municipal debt, affordable housing, and differential access to capital. Some will even point out that babo’s presence in itself does little to accelerate gentrification and that stopping babo will do little to stop the wheels of gentrification from turning.

It’s definitely true that that these questions are deep and complex and that we miss a lot by focusing solely on businesses we deem gentrifying. These problems are structural and the actions of folks with capital and disposable income are rooted in a system that is fundamentally inequitable.

Yet to suggest that the focus on new businesses is misguided is to dismiss the experience, knowledge, and politics of the people who have the most to lose. Yes, the rise of businesses catering to more bougie types is but a symptom of a larger problem, but as it is with any illness, the symptoms are precisely what alert us to a deeper problem in the first place. It’s not so much that new businesses and amenities are undesirable in and of themselves. It’s not like having more arts, music, culture, and food options is in and of itself a bad thing. It’s that these things usually signal (and even aid in bringing about) certain negative changes down the road. It’s that these new businesses and amenities are likely to draw in folks who could displace us. It’s that all these newer businesses (babo, Ma Lou’s, Cultivate, Go! Ice Cream, etc.) and amenities (like foot bridges, place-marking signs, and grass-mowing sheep) are things that we who are vulnerable to displacement might not be around all that much longer enough to enjoy. It’s that these newer businesses and amenities might come off as being only for privileged newcomers and not particularly welcoming or accessible to those of us who’ve been struggling to get by.

Those of us who are vulnerable to displacement understand that these visible markers of what’s euphemistically referred to as “change” are symptoms of forces and processes that are much bigger than the actions of individuals or groups of individuals. Yet we also know that when we see new businesses open, we see the advancement of forces that threaten our already precarious housing stability. When symptoms manifest themselves, we take note and we spread the word in hopes that gentrification becomes a bigger part of the public conversation. To talk about symptoms doesn’t mean that we’re not also talking about the disease. We’re talking about the symptoms because these are precisely what’s unbearable and conspicuous about the disease.

It is no coincidence then that the very same folks who insist that we not focus on new businesses as the problem are often the very same people who regard all this talk about gentrification as something new, and if not new, misguided, irrational, and mean spirited: these folks probably haven’t been feeling the symptoms in a way that signals any kind of threat to their own personal security or well-being. While they acknowledge that there’s a problem (usually after someone publishes a study or report on the matter), they feel on some level personally attacked by the ire directed at business owners because they identify more with economically privileged white entrepreneurs and consumers than they do with low-income folks whose housing is precarious. They would rather channel the conversation into the questions that most concern them and that are within their personal realm of competence (how to grow the tax base, how support entrepreneurship, how pay off the city’s debt, or other “positive solutions”). They understand that the municipal growth machine produces inequitable outcomes. But because they are professionally and affectively invested in the municipal growth machine, they would rather hope that things turn out alright for low-income folks than to center the lives and voices of the precarious in actively reshaping municipal governments to function more equitably.

It seems that the number one priority for many (including many liberal allies who claim to have the interests of their low-income “neighbors” at heart) is for Ypsi to pay off the Water Street debt. Yet it is likely that this will come at the expense of folks priced out by rising rents. For many “allies,” this displacement seems to be little more than an unfortunate side effect of progress, to be mitigated, perhaps, but not questioned in any way that examines the complicity of folks with capital and privilege in maintaining and acting in accordance with the dictates of the municipal growth machine. While many hope that “solutions” can be found to the problems low-income folks face in finding affordable housing, low-income folks quickly become a population to be sacrificed in the name of paying off the debt. And the way things are looking now, it seems like municipal debt is little more than a means of holding municipalities hostage so that they can’t help but cater to developers.

Simply put, it’s easy to be for “change” when you have something to gain from that change. It’s a little less easy when that change looks like it’s going to upend one’s already precarious life and community.

The desire to direct the conversation away from individual agents to matters of economics or policy is often driven by a desire to avoid difficult conversations about the ways in which oneself is implicated in gentrification. It’s understandable that people would want to avoid conversations that are uncomfortable. But justice isn’t served by ignoring the ways in which variously positioned people act in ways that feed a fundamentally unjust system. Too often people want to redirect the conversation to absolve themselves, to blame the people “over there” as the folks who are “really the bad ones,” or even worse, to make themselves look like heros (heros who promote job creation, are in favor of growing the tax base and spreading out the tax burden, who support affordable housing initiatives, and who add some kind of “value” to the community through their professional and commercial endeavors).

To understand the ways in which variously positioned folks are implicated in gentrification, it is important to understand how gentrification unfolds as a process. There are many frameworks for understanding gentrification, but it’s common to understand gentrification as something that happens in phases, with succeeding waves of newcomers and capital investment giving way to further waves. For example, in one high-traffic Ypsi Facebook thread, someone copied the following text from the Utne Reader website:

Artists generally lead the charge, always on the search for space that can be rented cheap. But they want atmosphere too—old buildings, places to walk, maybe a waterfront, and it can’t be too far from downtown. Then come the coffee shops, which draw writers and musicians, and the galleries. Gays come next, then young lefties, attracted to the creative energy but also seeking a connection to the folks who’ve lived there all along: African Americans, Latinos, hoboes, Eastern Europeans. An old tavern in the area begins booking alternative rock bands and offering microbrews on tap.[1]

With the exception of a certain details, this is pretty much true of Ypsi over the past decade (artists, riverfront parks, coffee shops, writers, musicians, and queers) and is a dynamic that is bound to expand and intensify as folks move into less white, less well-off sections of town.

Ypsi Real promotional materials capitalize on an image of Ypsi that’s in sync with these early phases of gentrification, craft beer and all:

Here you’ll meet the talented, the fascinating, the proud. Artists with the room to create. Entrepreneurs with the freedom to risk. Students with the arena to question. History buffs with the opportunity to explore.[2]

Of course as properties get bought and rented out and as property values and rents rise, room to create and freedom to risk will become increasingly rare. And history itself will have become forgotten and erased, both in minds and in the local landscape.

It is clear that Ypsi is at a turning point, with new spots in Depot Town, co-working spaces downtown, and the attention of international investors looking to develop Water Street. The Utne piece continues, pointing us to what happens when the process of gentrification continues:

At this point, many of the old-time residents are gone due to rising rents. Graphic design firms and architects set up shop, and word goes out that the area’s not so hip anymore. But more people keep coming. Starbucks opens. Ten-dollar cigars are on sale at the corner grocery. It’s very crowded on Friday and Saturday nights. Lawyers and investment bankers buy condos. The Gap opens. Restaurants offer valet parking. The city council talks about building a sports stadium nearby. Planet Hollywood opens. By now all of the artists have relocated to a nearby industrial zone or working-class neighborhood, where a new gallery/coffee shop/performance space just opened up in an old gas station. And the game starts all over again. . . .

While this description is not 100% applicable to Ypsi, particularly given Ypsi’s size (it’s hard to imagine valet parking, investment bankers, or a sports stadium or Planet Hollywood popping up in or near downtown Ypsi, though we’ve managed to imagine a multimillion-dollar “international village”), you have here the broad contours of the gentrifying process. Gentrification has a tendency to snowball and replicate itself as the reach of capital expands.

This is also reminiscent of the four stages of gentrification outlined in the 70s by MIT urban studies professor Phillip Clay. Peter Moskowitz outlines Clay’s first stage as follows in How to Kill a City:

[T]he first phase begins when individuals, unsupported by any government or larger institution, decide to begin moving into a previously poor neighborhood and renovating houses. National media [or in case of Ypsi, regional media] pay little attention, and any increase in the concentration of gentrifiers comes largely from word of mouth.

Many of us renters who came to Ypsi during early phases are now vulnerable to displacement. And many of us who moved to Ypsi during early phases are low income. Perhaps we have friends who are renovating houses east of Depot Town or just south of downtown. Perhaps we rent from a landlord who scooped up some foreclosed properties earlier this decade when rents were cheaper. But in paving the way for further gentrification (perhaps we are artists, musicians, or baristas upping the hip factor), we are like more privileged, higher income, more advanced-stage gentrifiers insofar as we are all swept up in processes bigger than ourselves, processes whose advancement we aid through our actions. Perhaps we’ve rubbed elbows with house flippers. Perhaps we moved here from predominantly white rural and suburban communities and then encouraged our friends back home to move here. Maybe we’re queers looking for community. Maybe we’re artists looking for a space to showcase our work or musicians looking for a venue for our band to play.

This is where Ypsi’s been. But where’s Ypsi going? Part of the proposed Water Street development includes condos along the Huron River, which during a recent presentation before the City Council were were revealed to be possible future homes for EB-5 visa holders (read: ‘millionaires’) who invested the development. Along with the development’s “luxury” student housing, it is quite possible that residents of this “international village” could then set their sights on surrounding neighborhoods. (Relatedly, the retort during babogate that Depot Town is “already gentrified” doesn’t quite allay the concerns that new businesses would be drawing in newcomers with disposable income who could subsequently take interest in other, less gentrified neighborhoods.) Gentrification is a domino effect, after all.

While the phases outlined by writers and scholars are more schematic than anything else and do not map perfectly onto Ypsi (or any flesh-and-blood 21st-century city for that matter), considering them is helpful. And in reality, a given city can be experiencing elements of disparate phases simultaneously. As in the case of the Water Street development that’s being pursued as a “solution to the city’s financial woes,” the draw of international capital to a smaller (and only moderately gentrified) city like Ypsilanti gives Ypsi something in common with hypergentrified global cities like New York and San Francisco: we’re already seeing global capital take an interest in Ypsi as a site for multimillion dollar development, though on a much smaller scale here than in these larger cities.

Gentrification, as we see, happens in waves. This is relevant when talking about how differently positioned folks are implicated in gentrification. Low-to-moderate-income people who come to a city or neighborhood in the early stages of gentrification are implicated in the process, but they are also vulnerable to displacement in succeeding phases. Moskowitz talks about not being able to afford to live in the heavily gentrified West Village, where he grew up. But in being displaced, he was also displacer, moving around New York, to Queens and Brooklyn. This domino effect shows that when it comes to gentrification, one can simultaneously occupy both positions of displacer and displaced, complicit but also vulnerable:

I was in some ways a victim of the process, priced out of the neighborhood I grew up in, but I also knew I was relatively privileged, and a walk through Bushwick or Bed-Stuy confirmed that—seeing the old, dilapidated apartment buildings under renovation on block after block, with windows boarded up and signs out front proclaiming the building’s new owners. I knew people were being kicked out. It became clear that for most poor New Yorkers, gentrification wasn’t about some ethereal change in neighborhood character. It was about mass evictions, about violence, about the decimation of decades-old cultures.

But the reporting I’d seen on gentrification focused on the new things happening in these neighborhoods—the high-end pizza joints and coffee shops, the hipsters, the fashion trends. In some ways that made sense: it’s hard to report on a void, on something that’s now missing. It’s much easier to report on the new than on the displaced. But at the end of the day, that’s what gentrification is: a void in a neighborhood, in a city, in a culture. In those ways, gentrification is a trauma, one caused by the influx of massive amounts of capital into a city and the consequent destruction following in its wake.

It’s difficult to report on the lives of people and communities being displaced by gentrification because “it’s hard to report on a void,” but also because displacement from one’s home tends to be regarded as a personal or private matter (and talking about one’s own experience of precarity can be a vulnerable thing to do). Shiny new businesses are alot easier to talk about. They’re more public and visible than the hidden lives of folks whose housing security is precarious. Yet sounding the alarm when a new spot opens is important because it’s not just that these new spots are conspicuous signs of gentrification to come: by changing the landscape, these new places change perceptions of Ypsi, which goes from being seen as run-down and shady to being seen as the cool place to be, thus feeding further gentrification.

Chances are if you are white and college-educated you are complicit, whether or not you have intended to be. This is something to own up to. But wallowing in guilt and defensiveness about it isn’t going to help anyone. Conversation should begin with an acknowledgment that one is implicated in (and even benefits, at least in the short term, from) these processes. A good way to build understanding is to acknowledge that one can be both vulnerable and complicit at the same time. This is because our actions are rooted in a system whose inequitable tendencies end up hurting most (if not all) of us somewhere along the line. Instead of taking up space in conversation seeking to defend oneself or absolve oneself of guilt, it is better to work to understand how the system works and to do so in a way that centers the concerns, desires, politics, and experiences of people who are most vulnerable to displacement.

Notes

[1] http://www.utne.com/arts/hip-hot-spots

[2] http://www.visitypsinow.com/ypsireal/

*

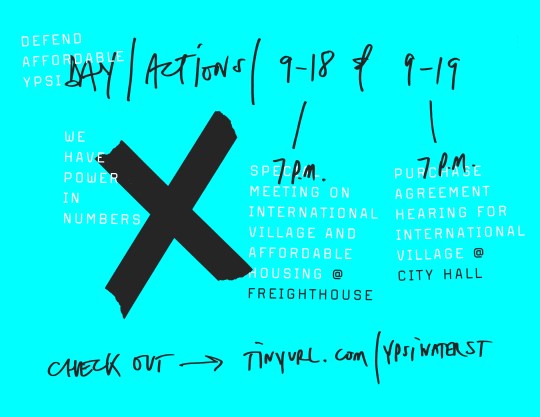

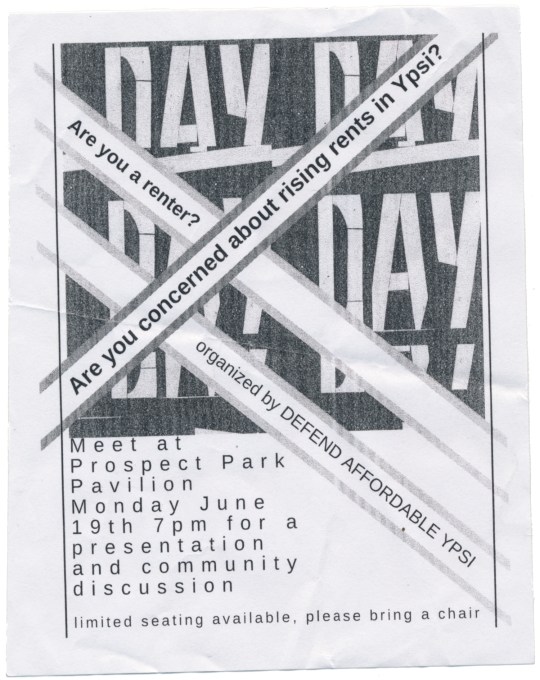

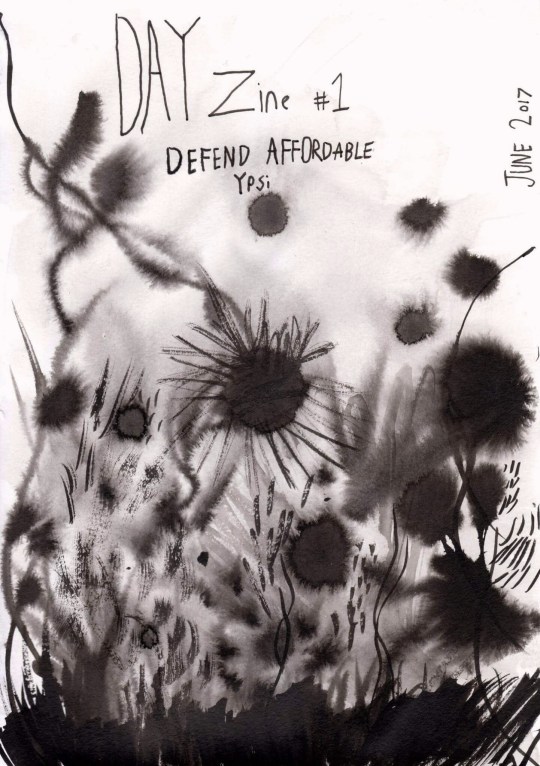

DEFEND AFFORDABLE YPSI is a social media project aimed at generating critical discussion around gentrification and affordable housing in Ypsi and beyond.

The task of DAY is to share news, commentary, audio, video, and other media on gentrification, displacement, affordable housing, and racial and economic segregation.

The DEFEND AFFORDABLE YPSI Facebook page is updated regularly and will serve as an ongoing archive, highlighting media from a variety of sources. DAY’s purpose is to inspire and assist the struggle to build a more equitable Ypsi through collective self-education and mutual empowerment.

In the coming months, DAY will be producing original content dedicated to exploring these issues in greater depth. This zine is the first effort toward this end